This article written by Melanie Lefkowitz originally appeared on the Cornell Chronicle on February 1, 2019.

When it comes to news, we believe what we want to believe – even though deep down we may know better.

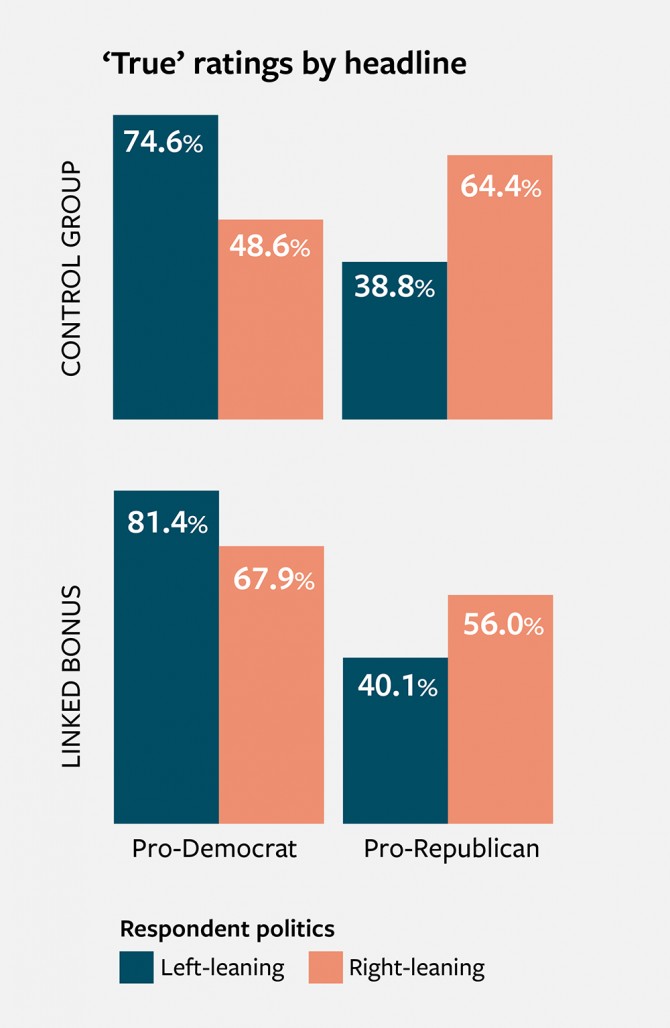

Cornell Tech researchers and colleagues have found that people are far more likely to say that news stories are true if they align with their own political views regardless of the outlet. But when offered a cash bonus for correctly evaluating the stories’ accuracy, participants were more likely to say they believed the news stories that countered their views.

A Cornell Tech-led study found that people tended to believe news story headlines were true when they aligned with their political views – however, when participants were offered a cash bonus if they evaluated headlines accurately they showed less bias.

“There’s an issue of expressive responding, where people say what they want to be true rather than what they actually believe to be true,” said Mor Naaman, associate professor of information science at the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech and senior author of “The Role of Source, Headline and Expressive Responding in Political News Evaluation,” which will be presented Feb. 1 at the Computation + Journalism Symposium in Miami.

Computation and Journalism graphic.jpg

In the study, researchers told participants that they’d receive a bonus if they guessed the accuracy of all the headlines correctly, “motivating them to say what they truly believe,” Naaman said. “People were suddenly more willing to admit that claims aligned with the other side were true.”

This effect was more pronounced for right-leaning participants than for those with left-leaning politics; Naaman said future research will explore why.

Maurice Jakesch, a Cornell Tech doctoral student in the field of information science, is the paper’s first author. Also contributing were Cornell information science doctoral student Anna Evtushenko and Moran Koren of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

The study is the first to test for expressive responding, as well as to examine trust in news outlets independently of trust in story content. Participants were asked to rate stories associated with The New York Times and Fox News, but the outlet where the story was said to appear did not affect their trust level, whatever their political orientation.

“The results are pretty clear: It’s not about people believing the Times vs. Fox News; it’s about whether the claim in the headline agrees with their view of the world,” Naaman said.”

The researchers recruited a diverse group of around 400 participants, evenly divided between right- and left-leaning in their political views. Each participant was shown two political headlines aligned with Democratic views and two aligned with Republican news, randomly assigned to either Fox News or the Times. They were also shown 12 other headlines that were not part of the experiment.

The political headlines – including “Trump lashes out at Vanity Fair, one day after it lambastes his restaurant,” and “Companies are already canceling plans to move U.S. jobs abroad” – were all true, but none actually came from the Times or Fox News. They were chosen based on previous studies that showed they were right- or left-leaning, and that readers had trouble ascertaining their accuracy.

Participants were given 15 seconds to rate each headline as true or false. The headlines could not be copied, making it impossible to plug them into a search engine. They were each paid $1 for about five minutes of work.

To determine whether they truly believed their answers, half the participants were offered a bonus of $1.60 if they correctly answered 12 out of 16 questions. (All participants in that group received the bonus.) The other half were in a control group.

Though further study is needed, Naaman said the findings have potential applications for news aggregators, which might focus on balancing news feeds politically by content instead of merely by news outlet, or social media sites, which could incentivize people to only share stories they trust.

“We’re living in an age of misinformation, where it’s very hard for people to distinguish between established and trustworthy and credible news organizations,” Naaman said. “Understanding how people make decisions in online news when it comes to the stories they read and how the react to them is important, so that we can design information systems and presentation systems that support trustworthy sources above others.”

The research was supported by Yahoo Research and Oath, which is part of Verizon Media Group, through the Cornell Tech Connected Experiences Lab.